ACLU-MO Early Years: 1930s

The St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee began on May 7, 1920, with about a dozen volunteers, both men and women. For its first decades, the group and its actions remained focused on advocacy and education about civil rights.

By 1932, the national ACLU noted that St. Louis was focusing “chiefly on two issues — the conflict between police and unemployed demonstrators, and the strike of coal miners in Illinois.” In the local chapter’s earliest brochures, volunteers noted they “maintained a persistent interest in the encroachment upon the rights and liberties of citizens by illegal and improper police practices.”

The 1930s

Early on, the St. Louis Committee mainly focused on investigating and raising awareness through educational programs. When funding could be secured, they went to court on behalf of those arrested while exercising their rights to free speech and free assembly.

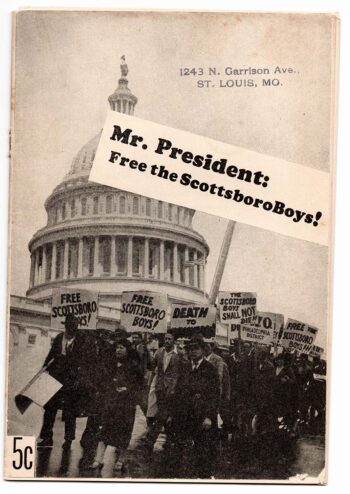

In June 1932, the St. Louis Committee appealed the conviction of two men charged with destruction of property because they posted flyers organizing a local protest meeting over the arrests of African-American teenagers in Scottsboro, Alabama. Few records remain from these early years, but the national ACLU did send funds to help with court costs. The names of those arrested, however, are not listed, making it difficult to locate further information about the case.

Ralph Fuchs, president of the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee and a professor of law at Washington University, described what he saw at the protest:

“As an eye-witness to what took place, I wish to say in this open letter that in my judgment, the responsible police authorities own an apology to the citizens of St. Louis because of the trampling upon American rights and the consequent danger to American institutions which characterized police handling of an American Workers’ Union demonstration …Prior to the arrival of a patrol load of police at the scene of the disturbance the conduct of everyone concerned with the ‘workers’ ‘ demonstration was beyond criticism. The police previously on duty were tolerant and decent, and at their request the way was kept open for all traffic, vehicular and on foot. For the most part, the crowd of 500 or more was quiet, although a few were singing….There was no disturbance of any kind. Then the brutality began.

Apparently under orders to clear the walks, the police from a newly-arrived patrol started rudely and with the use of clubs to clear the sidewalk…As the crowd dispersed to the east and across a vacant lot, the police pursued them, using rough tactics and bad language towards such as stood their ground or talked back. A number of arrests were made. After the crowd had gone, innocent individuals, standing alone, were illegally ordered to leave…As an individual and on behalf of other members of the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee, I wish to protest most emphatically against your conduct… I do so with full appreciation of the difficult role the police are called upon to play and with the continued belied that on the whole they perform their duty conscientiously and well.”

Read the full text of his letter, originally published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

St. Louis Situation

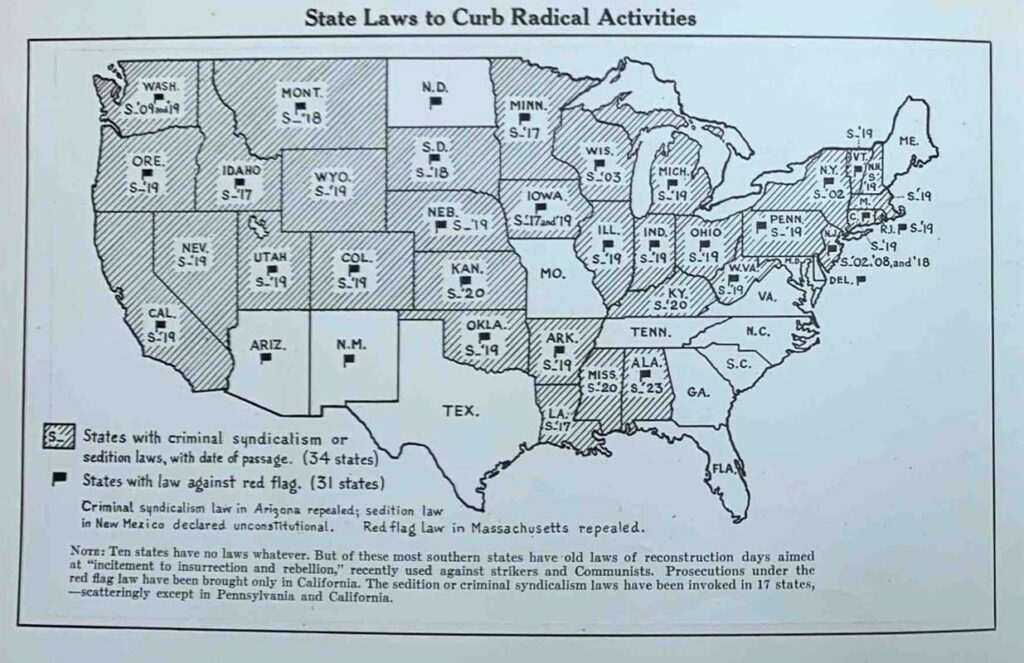

Compared to other parts of the United States, the St. Louis area, and Missouri in general, did face fewer civil liberty challenges in the 1920s and early 1930s. The primary exception to this was in the area of policing.

And criminal justice reform and ending the abuse of police power remain key areas of policy focus for the ACLU-MO in the 21st century.

More

- Read more newspaper coverage about the ACLU in Missouri during the 1930s from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

- Library users with a WUSTL key can also access the full issues via ProQuest, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (1874 – 2003).

ACLU-MO @ 100

This post is part of a series in recognition of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri’s centennial year (1920-2020). Read more stories at the following link: ACLU-MO @100 in Our News

If you have a question about this post or other topics related to St. Louis history, I can be reached at mrectenwald@wustl.edu or on Twitter: @mrectenwald.