ACLU-MO and Racial Justice: 1940s

ACLU-MO in the 1940s

In the years before World War II, the was a small organization. In March 1940 St. Louis had

Of these, the focus on rights for African Americans stands out, and makes the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee one of the earliest (majority) white organization in St. Louis to actively work for racial justice.

Partners

Starting in the 1940s, the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee began working with the local NAACP and Urban League chapters on civil rights efforts. This followed the pattern established by Roger Baldwin founding the ACLU, ensuring that work on “inter-racial questions” was done in coordination with African American-led organizations.

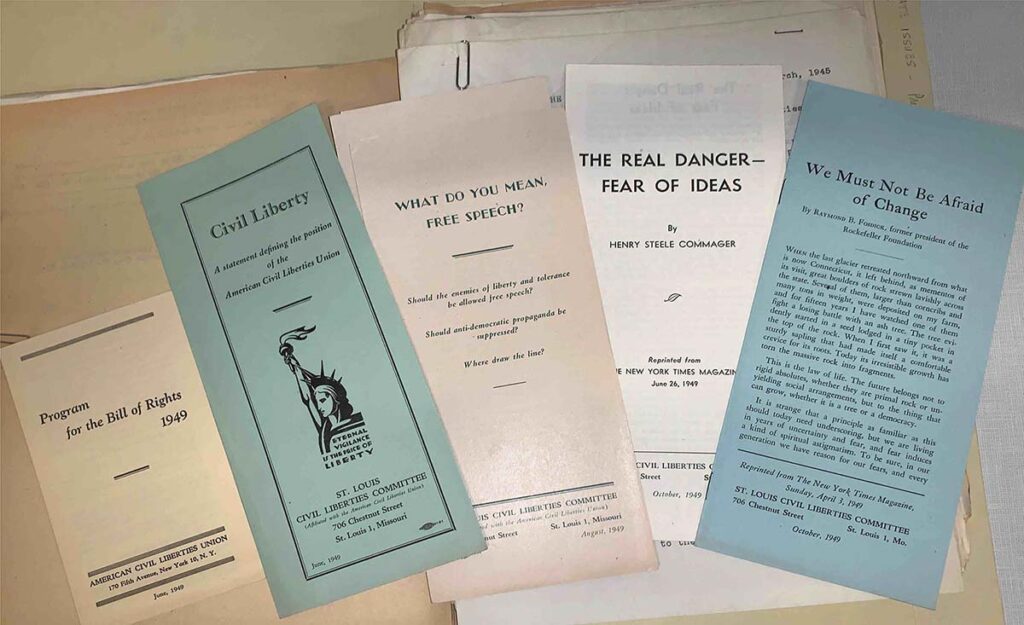

This racial justice work took several forms. One was awareness. For instance, when planning the 1940

The investigation continued to show the gross injustices African Americans met at the hands of police and the criminal courts. And the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee took a further step in 1947 when they supported the US Supreme Court case Shelley v Kraemer, aimed at ending segregation in homeownership.

Criminal Justice

As in the 1930s, the main action taken was investigation. In 1942 the St. Louis committee called an emergency meeting to discuss the lynching of Cleo Wright in Sikeston, Missouri (150 miles to the south). A volunteer was sent to Sikeston where the NAACP was investigating, but it was ultimately determined there was little with which the civil libertarians could assist.

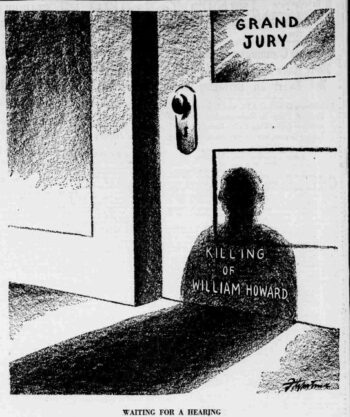

In some cases they became more involved, such as following the tragic death of William Howard in 1946. An African American Army veteran, Howard was shot and killed by William Niggeman, a white off-duty police officer after an argument in an alley. Soon questions surfaced of he FBI investigated, but in late 1947 declined to take any action, since no federal law was broken. Niggeman faced no criminal charges, but did resign from the force.

Segregated Housing

George Vaughn even without national approval. They recognized that as an experienced African American lawyer in St. Louis, Vaughn was well-informed

Continuing Efforts

In the following decades, the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee’s focus on racial justice continued. It greatly expanded in the 1950s and 1960s as the civil rights movement grew across the nation. Now, in the 21st century, racial justice continues as a key focus of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri.

More

- Dominic J. Capeci, Jr., The lynching of Cleo Wright (University Press of Kentucky, c1998)

- “FBI to Investigate William Howard Case” Chicago Defender 11/23/1946 page 19

- Shelley v Kraemer (1948)

- Jeffrey D. Gonda. Unjust deeds: the restrictive covenant cases and the making of the civil rights movement. (University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

ACLU-MO @ 100

This post is part of a series in recognition of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri’s centennial year (1920-2020). Read more stories at the following link: ACLU-MO @100 in Our News

If you have a question about this post or other topics related to St. Louis history, I can be reached at mrectenwald@wustl.edu or on Twitter: @mrectenwald.